Large companies will face insurmountable difficulties in transforming themselves if they do not have someone who can drive the digital acceleration process from where all the biggest decisions are made: The board of directors. Many boards lack the necessary background or knowledge to tackle this challenge. The main obstacle is not the age of board members, as is the usual assumption, but rather their level of expertise in technology and in the ways of thinking and doing that are being implemented by their disruptive competitors.

INTRODUCTION

Many are already stating that the great accelerator behind the digital transformation of our lives and institutions has been COVID-19. In transcripts of recent investor presentations from Spanish companies operating in the open market, one common mantra is repeated time and time again: “We have suffered the consequences of the pandemic across all levels. Our teams have learned to work remotely, and technology has allowed us to operate resiliently in all aspects of the business. Over these months, our business’ digital transformation has advanced at unprecedented speed.”

It is true we are witnessing a paradigm shift, the depth of which we will need time to measure. People’s communication, consumption, and mobility habits, as well as essential details of daily life in organizational structures, are changing – perhaps forever. However, though we are witnessing this transformation with our own eyes and have seen how organizational responses to the pandemic’s challenges have been positive, it is dangerous to fool oneself into thinking that this digital transformation is a done deal. Perhaps there has never been a better time to question our companies’ levels of preparedness when it comes to adapting to and leading these changes.

An initial list of uncomfortable questions for anyone leading an organization in these modern times could be:

- What will the new normal mean for our consumers, and which aspects of the changes we have seen will be accelerated?

- Which companies are best capitalizing on these changes? What are they like? How do they do business?

- Which (as of now, just emerging) companies are going to challenge our product and service offering in this new context? Which technology assets will they use to transform the sector ecosystem?

- Which burgeoning business models have the most potential to consolidate themselves?

- Which exponential technologies will have the greatest impact on our sector over the next 5, 10, and 15 years?

These questions are already floating around within informal circles at companies, with varying degrees of impact. However, in more formal circles, it is highly likely that few people have dared to speak fearlessly about the elephant in the room.

Who is in the position to ask those questions, get to the bottom of the answers, and make significant decisions at large organizations?

“Though we are witnessing this transformation with our own eyes and have seen how organizational responses to the pandemic’s challenges have been positive, it is dangerous to fool oneself into thinking that this digital transformation is a done deal”

BOARDS, THE DIRECT MANAGERS OF CHANGE

By examining the experiences of industries that have survived various disruption cycles (the media, entertainment, financial services, telecommunications, and others), we can recognize three omnipresent laws of transformation:

- Digital disruption recognizes no boundaries and eventually touches all sectors.

- There is already a painful but undeniable historic record: Leading executives at organizations in sectors that primarily change defensively tend to resist those changes, and when they eventually accept the need to innovate, it is too late.

- Talking about digital transformation is not the same has having taken it on board and making the right decisions before change arrive. The frequency and volume of discourse about future changes at an organization can be inversely proportional to the reality of what is actually happening at the heart of the company.

This phenomenon has been scientifically studied by authors such as Clayton Christensen (The Innovator’s Dilemma); Peter Sufton (The Knowing-Doing Gap); and Heifetz, Grashow & Linsky (The Practice of Adaptive Leadership). Two illustrative examples can be found in works by the thinkers Paul Saffo (Stanford) and John Hagel (Deloitte Digital), both of whom write from a perspective that combines research and consulting.

To briefly summarize what these authors say and what our own professional experience tells us, organizations – regardless of the sector in question – go through something very similar to the five stages of grief:

- Denial: “This won’t change, we’re too big.”

- Anger: “Who do these Silicon Valley upstarts think they are?”

- Bargaining: “Something needs to be done, let’s call the consultants.”

- Depression: “Why don’t investors believe in our model anymore?”

- Acceptance: “We had the opportunity to change but we didn’t see it.”

What makes it so unusual for large companies with a history, strong brands, and a sound market position to lack the necessary flexibility to tackle change? The answer to this question has led to its own discourse, but everyone can think of reasons stemming from common sense and experience:

- Fear of change affects institutions just as much as it does people.

- Figuring out when emerging changes will become widespread is difficult. Change will come, but many do not know how to anticipate when. This jeopardizes the futures of companies.

- Paradoxically, cash flow can be a serious enemy of innovation. Many companies do very well up to the point when change becomes insurmountable.

- The incentives that make the machinery turn.

- The power of the day-to-day, the here and now. When an organization stays within its comfort zone or fails to invest time in reflecting on latent threats, it moves onto thin ice.

- The struggle to stay afloat. Organizations sometimes face major and very pressing problems, entering survival mode for reasons such as accepted debt. It is very difficult to think about the future in that situation.

- Finally, but no less importantly, a company’s internal culture can wither away during a sector-wide disruption if suitable measures are not implemented on time.

“One key aspect all these organizations have in common is the composition of their boards of directors and the level of involvement from certain board members in the sector’s future outlook, the impact of technology, and the business innovation process”

Is it therefore inevitable that a traditional company will succumb to change?

In the majority of cases, what eventually happens is that traditional companies finally merge with new ones, transferring their assets to new investors or continuing to operate for a few decades without their past vigor.

However, there are some exciting examples of large companies that have successfully adapted across several cycles of disruptive change. In some cases, they were on the verge of disappearing before an audacious leader, new vision, and board of directors with the right ingredients reached an agreement to turn the status quo around.

One key aspect all these organizations have in common is the composition of their boards of directors and the level of involvement from certain board members in the sector’s future outlook, the impact of technology, and the business innovation process.

Home improvement chain Lowe’s and the technology company Apple represent two examples of this in action.

Lowe’s was facing the threat of online operators, such as Amazon. This led to a strategic turn-around promoted by the board of directors that has resulted in a five-fold share price increase since 2016. The history of Apple, which was on the verge of bankruptcy in 1997, is even more famous.

In both cases, the board made transformative decisions for the organization that could only be implemented and followed up on by the authority of the company’s highest governing body.

In both cases, before implementing this turn-around, they decided to incorporate digital board members who had in-depth knowledge of the technological changes affecting sector development and consumption.

And in both cases, the boards managed this change directly, overcoming internal pushback and taking strength from two ingredients sometimes considered incompatible: Human maturity and technological know-how. Silicon Valley legend Bill Campbell encouraged Steve Jobs to make radical decisions for Apple. Laurie Douglas, one of the greatest U.S. experts in Large Retail Technology, gave Lowe’s CEO a definitive argument for transforming the shopping experience at its stores by applying a far-reaching innovation process.

The current reality facing many listed companies around the world is that their boards lack the digital expertise necessary to measure the information they receive from their senior management team regarding the degree of success in their digitalization process. For that reason, they lack sufficient information to question the level of ambition in the initiatives deployed or properly understand the threats posed by emerging changes.

Is it a question of age? Is it possible that the digital gap created by the year someone was born can be responsible for these shortfalls in the boardroom?

One way to test this hypothesis is to take a look at the boards of directors in U.S. Big Tech companies. We have done exactly that, and the results are incredibly revealing.

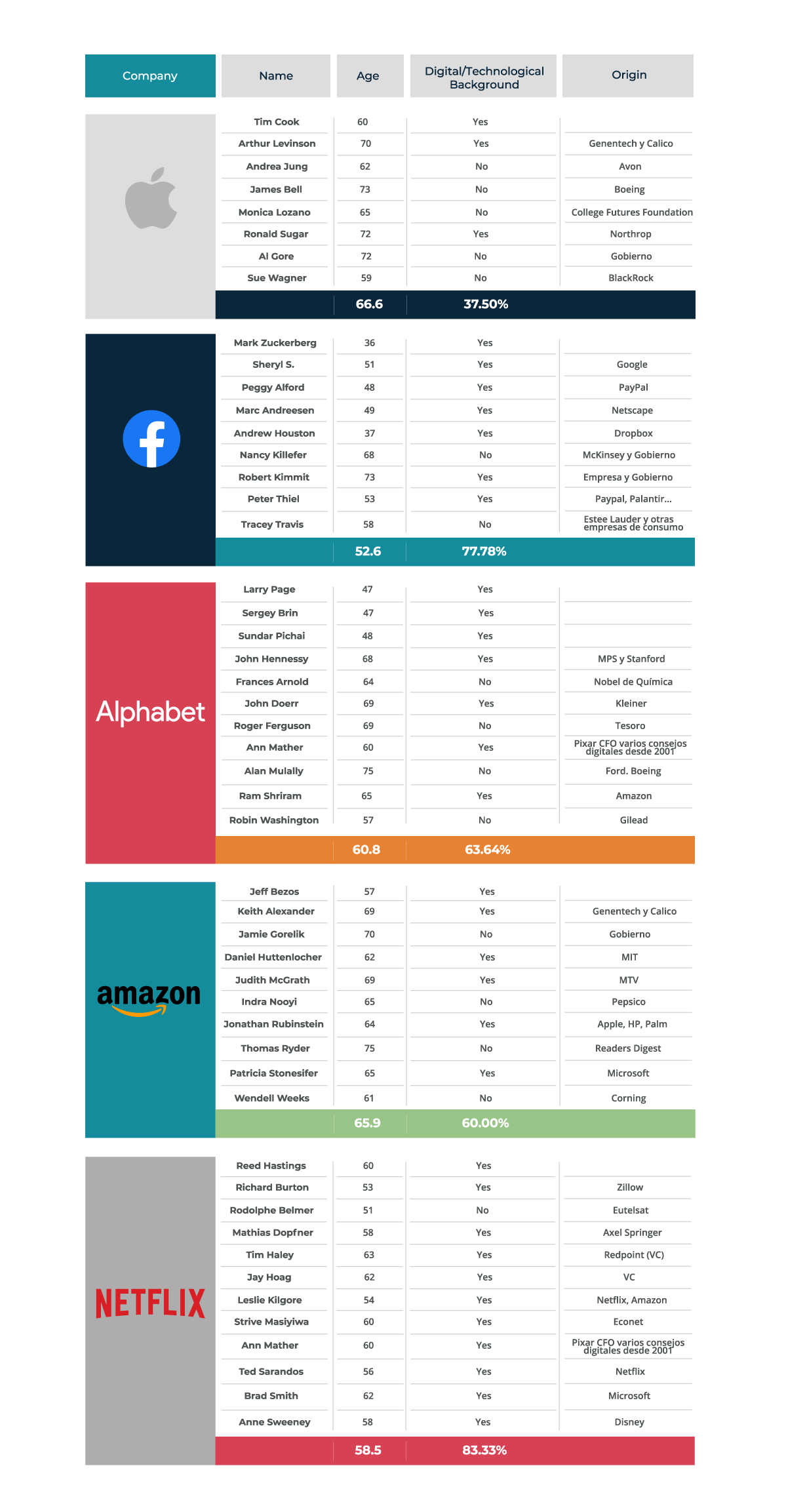

The average age of board members at Apple – the most valuable company in the world – is 66.5. Amazon’s board of directors has an average age of 66. Facebook’s is younger, with an average age of 53.

What differentiates the boards of directors at these large tech companies from other traditional companies is not age; it is their members’ level of technological and digital expertise. As you can see in the table below, a large majority of board members serving at these companies have experience in managing tech companies, are experts in a specific field of computing, or represent risk capital firms with extensive experience in financing tech startups.

“The current reality facing many listed companies around the world is that their boards lack the digital expertise necessary to measure the information they receive from their senior management team regarding the degree of success in their digitalization process”

INCORPORATING DIGITAL TRANSFORMATION INTO THE BOARD OF DIRECTORS

Before making specific decisions in this regard, companies must first consider which aspects of the transformation process require the most attention from the board.

One key issue is that the board should adopt a realistic position regarding the company’s future, opportunities, and threats. In this regard, outside voices will be important, specifically those of knowledgeable, independent experts who can convey this input in a language the board can understand. These people can independently measure the company’s competitive stance in the new context and assess the real value of the commitments being made.

Using this information, the board should be able to define basic parameters with which to measure the company’s situation during its transformation process, providing them with direct knowledge of the main milestones management is proposing. This will lend rigor and a sense of urgency to the changes.

Finally, certain technological issues are gaining increased value for companies (in terms of risks), and these should also be considered in the boardroom. Data protection, cybersecurity, and regulatory frameworks governing digital business should all be included in this consideration.

When deciding how to incorporate a digital mindset into the board of directors, at least three elements should be considered:

- Digital board members

The role of “Digital Director” has emerged in recent years. These professionals, who have extensive experience in disruptive businesses and sectors, know the lay of the land regarding the many changes and opportunities stemming from the technologies that will grow exponentially over the coming decades. They have their own way of thinking about their companies (the digital mindset), which consists of five basic components:

- The digital product management model.

- Cultural elements at this type of company, including team autonomy, flexible decision making, and constant experimentation.

- Technologies and capabilities necessary for developing scalable models.

- Data as an essential asset.

- The growing impact from Artificial Intelligence.

- Digital transformation committee

Aside from incorporating board members with digital expertise, another way of adding value to boardroom innovation is to create a specific committee dedicated to transforming the business. Ideally, this body would define the parameters used to measure the process and be responsible for measuring the degree of project implementation and proposing necessary changes.

- Within the board of directors itself

Based on the authority given to them by their shareholders, boards of directors have historically held certain basic responsibilities, such as appointing the CEO and approving company mergers and acquisitions, treasury stock levels, or remunerations policies.

Thought must be given to how business digitalization is shaped or, in a broader sense, what impact exponential technologies will have on the future of the product, sector, and company.

Because only the board of directors can clearly and decisively advance toward the future and prevent an ever-transforming world from replacing the valuable legacy handed down from their predecessors.

“Um aspecto fundamental é que o Conselho seja realista sobre as oportunidades e ameaças que a empresa enfrenta em relação ao seu futuro”

Authors

Alejandro Domínguez