IBEX 35 companies are beginning to consolidate their reputational risk management, recognizing it as a new type of risk.

An analysis by LLYC’s Leadership and Corporate Positioning team reveals that 91 percent of IBEX 35 companies now include reputational risk in their latest Annual Corporate Governance Reports (ACGR).

Good governance drives reputational risk management

The main factor driving boards of directors’ interests in reputational risk are the many corporate governance recommendations made in the last five years. According to these good governance recommendations, 88.6 percent of IBEX companies mention corporate reputation in their Boards of Directors’ Rules and Regulations in relation to the proper conduct of board members. Boards are primarily concerned with board members’ behavior of companies state they have rules in place that compel board members to report and resign in cases in which their membership may jeopardize the company’s standing and reputation.

Recommendation No. 53 in the Code of Good Governance places reputation among the company’s non-financial risks. It goes on to say reputation must be evaluated by the board through its commissions (Auditing, Appointments or CSR).

In terms of management tools, COSO (Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Comission) has established itself as the frame of reference.

What is reputational risk?

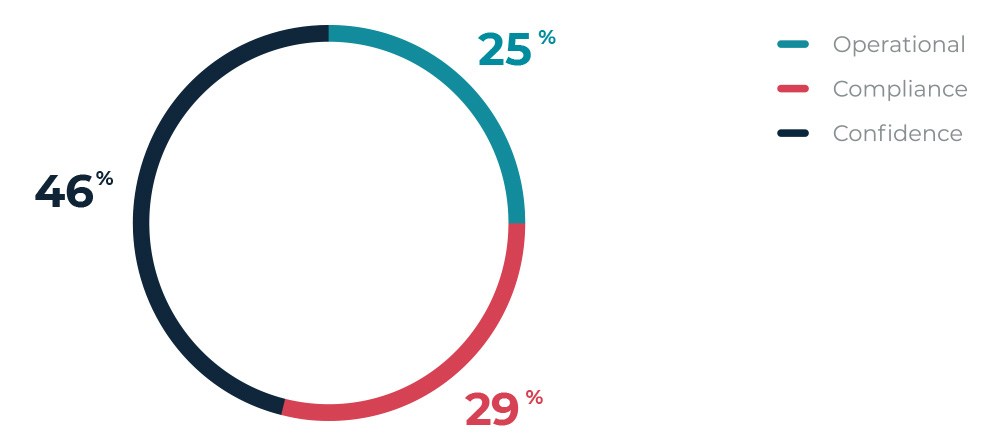

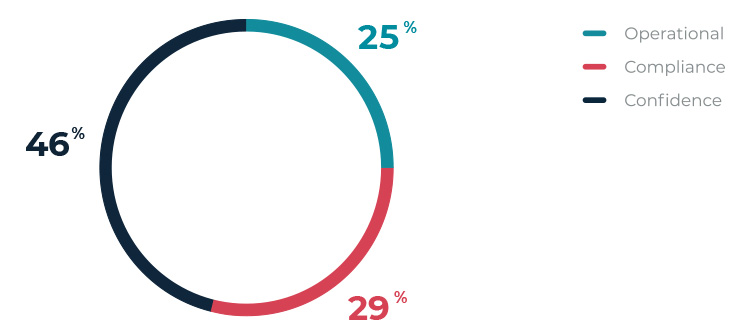

As a first conclusion, we can say IBEX 35 companies have fully incorporated reputational risk management. Many IBEX 35 companies use one of three main definitions:

- Reputational risk as compliance risk. Almost a third of companies define reputational risk in terms of compliance.

- Reputational risk as a byproduct of operational risk. Around 25 percent of IBEX 35 companies define this type of risk in terms of operational risks.

- Reputational risk as strategic risk, in relation to managing stakeholder confidence. Some 46 percent of companies (mainly financial) define reputational risk as “environment risk,” referring to external factors or events related to the political and social environment.

Financial companies are those developing a more advanced concept of reputational risk, given the specific good governance guidelines defined by the European Banking Authority (EBA). It also suggests possible causes of reputational risk, establishing many of them in the area of social beliefs and expectations. Therefore, according to the EBA, reputational risk must be reflected by strategic risk markers rather than operational or legal ones.

Reputational risk management trends

In our opinion, the EBA’s proposed strategic vision for reputational risk is more in line with the new VUCA (volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous) business environment.

This paradigm change, has undoubtedly caused drastic changes throughout the social ecosystem on the level of shared beliefs. It is important to highlight the emergence of new reputational risks, such as:

- Activist causes, such as the integration of diversity, protection of the planet and animal rights.

- Risk by association. New models of competition multiply reputational risks by association.

- Cyber risks. Digitalization permits models with large-scale impacts on shared beliefs.

- New ethical dilemmas. The digitalization of society and the economy is accompanied by new ethical dilemmas.

- The absence of a long-term corporate purpose or vision to explain how companies intend to distribute value among their various stakeholders.

“IBEX 35 companies have fully incorporated reputational risk management”

But it is not only the emergence of new kinds of reputational risks that is new; their impact as a consequence of emerging stakeholder behaviors is new as well. They form what we call “new reputational syndromes,” and they include:

- The anesthesia effect. This is a result of a tired society. This effect consists of an apparently lower impact from risk in the short term in consumer and/or investor behavior, although its effects materialize over the long term.

- Structural distrust and hypertransparency. In the 21st century, humans are becoming accustomed to living in low-trust environments. The disappearance of trust encourages the growing use of surveillance and control systems. One of the most punished reputational faux pas at present is “corporate falsehood” or the concealment of relevant information.

- Transfer of responsibility. Since the start of the economic crisis, social unrest and subsequent legal responsibility has been shifting from corporations to their managers.

From compliance to reputation

In light of these trends, we have to ask: Are IBEX 35 companies really prepared to anticipate today’s many new reputational challenges? In our opinion, many large companies still understand reputational risk as solely the reputational impact of their operational risks. Consequently, the challenge lies in moving from compliance to more integral corporate reputation management, going beyond compliance with good governance recommendations and allowing companies to anticipate new challenges to their reputations, especially those that affect large public companies.

Based on the reputational risk management and corporate empathy model we promote at LLYC, we propose the following recommendations:

- Sufficient risk understanding. It is necessary to broaden the focus of listening and analysis beyond the traditional model.

- Focus on the proper diagnosis of beliefs and expectations (emotions and attitudes). These are the basis of trust and, therefore, are a critical point of reference for reputational risk management. This is fundamental to, among other things, determine elements such as the company’s reputational risk tolerance.

- Prudential rather than accounting discipline. Reputational risk management must preserve the prevalence of the strategic focus over the accounting focus.

- Convert risks into opportunities. A proper reputational risk management model can undoubtedly be a factor in generating investor confidence in the company’s control systems.