One year and one day after he started his term, LLORENTE & CUENCA Peru reflects on The Dreams of President Kuczynski. At that time, two potential scenarios were discerned for how the country could evolve. On the one hand, possible peaceful political coexistence between the PPK and Keiko Fujimori that would assure stable governing conditions and sustainable economic growth and, on the other, a state of permanent conflict between the legislative and executive powers that would cast its shadow over political stability and private investment.

Today, one year after analyzing these two possibilities, we know that the difficulties in managing to create harmonious coexistence between a government without parliamentary support and an opposition with legislative majority is one of the reasons for the growing censure that Pedro Pablo Kuczynski has been suffering.

The LLORENTE & CUENCA LatAm Public Affairs team has prepared an assessment that not only analyses the main factors that have caused the political turbulence that Peru has experienced, but also considers a new outlook for his second year of mandate. This analysis sets out the main milestones that have shaped this first year of the PPK government, and that marks the course for what could happen in the next, an analysis that is essential for understanding what is actually taking place in Peru.

Luisa García, Partner and COO of LLORENTE & CUENCA in Latin America.

Luis Miguel Peña, Partner and General Director of LLORENTE & CUENCA in Perú.

A YEAR OF PPK

President Pedro Pablo Kuczynski’s first year was intense. The optimism at the start of his term, due to generating positive expectations in the business sector, slowly started to fade away as the economy underwent a deterioration triggered by strong political pressure. However, only days into the second year of the PPK administration, the possibility of better understanding between his government and the opposition, led by Keiko Fujimori, who controls the Congress, opens up the prospect of a recovery of optimism due to the eventuality of a better business climate in Peru. In light of recent months though, this optimism will remain cautious, as this five-year political term will never be free from complexities.

OPTIMISTIC START

At the end of an intense electoral campaign whose outcome was uncertain until the very last week, with PPK winning by fewer than 50,000 votes over Keiko Fujimori, there were quite positive expectations both from citizens and private investors.

In the business sector, because this was the first time in decades that the second presidential round was contended by two candidates who both looked favorably on private investment, and because the composition of the new Congress made one think that there would also be a friendly stance toward promoting private enterprise.

But the election results in 2016 entailed another novelty for the Peruvian institutional system. It was the first time in many years that a single opposition party—the Popular Force—gained a crushing majority in the Congress that would let it control the legislative process and closely supervise and monitor the government via the instruments established by the Constitution.

“The optimism […] slowly started to fade away as the economy underwent a deterioration triggered by strong political pressure”

These factors all made it clear that the main challenge in the 2016-2021 term of office would not be economic, given the similar outlooks of the main parties represented in Congress, but essentially political: How to articulate harmonious coexistence between a weak government like PPK’s, due to its scant parliamentary representation, and a solid opposition like that led by Keiko Fujimori, in light of its overwhelming majority in legislative power.

Thus at the outset of PPK’s government in July 2016 one could outline two basic scenarios for how the country would evolve.

On the one hand, the optimistic scenario, which would entail the establishment of basic political agreement between PPK and Keiko Fujimori that—without ever becoming a stable and permanent alliance—would let propitious conditions for governance be established, helping to set in motion the implementation of pending reforms to promote economic growth and improve quality of life in areas including the job market, the pension system and decentralization.

On the other hand, the pessimistic scenario, consisting of growing stand-offs between the government and the opposition that could place governability at risk due to the creation of an institutional impasse. This could cause the mandate to lose due to the permanent duel between those seeking presidential vacancy and those wanting to dissolve the Congress.

IMPASSE IN THE CONSTITUTIONAL DESIGN

The underlying cause of this impasse is a problem in the design of Peru’s political system, which was analyzed well by electoral affairs analyst Fernando Tuesta, who observed: ‘Peru is the only country in the region in which—being presidential—mechanisms are embedded that are typical of parliamentary systems inherited from Europe, creating a hybrid that has negative effects on Peruvian politics.’

He adds: ‘In parliamentary systems, the government is elected in parliament by a majority of a party or coalition of parties. While it does exercise a function of political control, the government can govern and the parliament can supervise its work. There cannot be a government with a majority parliamentary opposition.’

Thus, in a situation like the one Peru is going through today, the Fujimori opposition, due to having a huge congressional majority, can censure ministers as often as it likes, something that would be uncommon in a parliamentary system in which if the government lost majority, the prime minister would be directly censured and the elections moved forward.

CLOUDS OF THE HORIZON

At the start of his mandate, the opposition expressed support critical to the PPK administration, including a record and nearly unanimous investiture vote by Congress of the ministerial cabinet led by Fernando Zavala—as required by the constitution—as well as granting legislative powers to the government.

Nonetheless and one year later, the great difficulty is apparent in establishing elementary harmony between the PPK government and the Congress dominated by Keiko Fujimori’s party. This has frequently seen them taking the negative road of discord described above, darkening political stability and the business environment.

This was the consequence of the opposition outlining a complicated and often aggressive relationship with the government, which was clearly expressed in the censure at the end of 2016 of minister of Education Jaime Saavedra.

Ollanta Humala y Nadine Heredia: la resolución del juez Concepción Carhuancho bajo el análisis ► https://t.co/d7BIEVdD2e pic.twitter.com/ePfzCjLqZw

— Política El Comercio (@Politica_ECpe) July 15, 2017

The growing clashes between the government and the opposition were not the only source of complications for the country’s institutions and economic endeavors.

Other menacing factors have included the accusations of corruption of politicians and officials from the Operation Car Wash (Lava Jato) case in Brazil, which led to an international arrest warrant being issued for former President Alejandro Toledo; along with other denunciations, ex-President Ollanta Humala and his wife Nadine Heredia have been ordered preventative detention for 18 months; and this could also affect ex-President Alan García and former candidate Keiko Fujimori for having allegedly received illegal election contributions from the company Odebrecht.

There was also the strong impact of the coastal El Niño, with landslides and flooding causing severe damages to the national infrastructures and family estate, especially in the north of the country.

Finally, there was the lamentable action of the Republic’s comptroller general Edgar Alarcón, whose performance damaged the economic process. Its apex was the recording of private conversations he held with ministers, which were later leaked to the media in the context of the debate on the Chinchero Airport project in Cusco.

“The growing clashes between the government and the opposition were not the only source of complications for the country’s institutions and economic endeavors”

As a consequence of the political turbulence surrounding this project, and in the midst of heavy parliamentary pressure, the minister of Transport and Communications Martín Vizcarra stepped down—who is also first vice-president—as well as minister of Economy and Finance Alfredo Thorne.

The broadcasting of the aforesaid conversations also put Congress’s attention on the president of the Council of Ministers, Fernando Zavala. In the end, the comptroller was dismissed by the Congress of the Republic.

ECONOMY UNDER POLITICAL PRESSURE

The evolution of the economy and business climate in the country were among the main factors affected by rising political tensions in the first year of government of President Kuczynski.

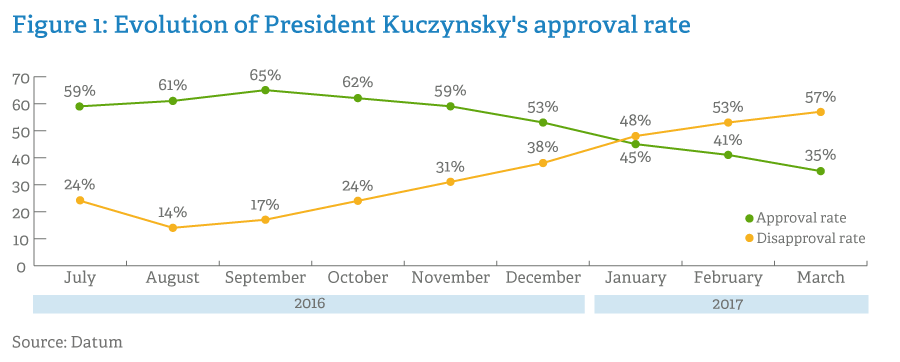

To start, public opinion approval on President Kuczynski’s performance dropped, according to Ipsos, from 63 percent in September 2016 to 34 percent in June 2017, while disapproval leaped from 17 percent in September 2016 to 58 percent in July 2017.

The consequences of the political stalemate between government and opposition, along with natural disasters, Operation Car Wash and the comptroller general’s actions have all led to virtual paralysis in public sector investment and spending decisions, and an unstable political panorama that has damaged investment decisions in the private sector, all of which has resulted in lower economic growth and worsening business expectations.

The Economy and Finance Ministry once again in July reduced GDP growth forecasts for 2017, now standing at 2.8 percent, a considerable drop compared to forecasts at the beginning of the year.

As a consequence of the negative effect of the political arena on the economic panorama, the expectations of both people and companies have been severely damaged.

“Public opinion approval on President Kuczynski’s performance dropped […] from 63 percent in September 2016 to 34 percent in June 2017”

On one hand, according to the Datum poll in July 2017, 70 percent of Peruvians believe that the economy is worsening, the highest rate yet during PPK’s government. The prevailing sentiment in public opinion is that the economy has come to a standstill, and that possibilities of finding jobs continue to reduce.

On the other hand, investment prospects have also weakened, which has been building up for several years now. The president of the Peruvian Institute of Economics (IPE), Roberto Abusada, points out with great concern the economic trajectory of the last four years:

‘Thus, private and public investment started the long and inevitable process of collapse due to misrule. All of these misfortunes were masked by the prosperity generated by high mineral prices and the boost from industry and the services sector that occurred during the construction of the mining megaprojects. Today, there is not only no investment in new mining projects or in production infrastructure, but this absence is being reproduced in the discouragement and paralysis of literally thousands of endeavors of all sizes, in which the true invigoration of the economy rests.’

Acceptance that the Peruvian economic situation is breaking down is assumed not only by the political opposition but also by President Kuczynski himself, who just pointed out self-critically that ‘I thought I could do more in my first year of office:’

‘We were going to grow by four or four and a half percent, yet we are at three percent. Operation Car Wash has eaten up one point and the coastal El Niño another half a point. This is what the people feel. Of course, nobody foresaw that Car Wash would be as disastrous as it was. It was one thing in Brazil and then it landed here and the accusations commenced against former presidents and companies and this has depleted trust. We had to cancel extremely large contracts: the southern gas pipeline, the motorway to Chosica, Chavimochic 3. Other projects that have nothing to do with Operation Car Wash, like the Metro Line 2 and the airport (Chinchero), also had problems. If the natural disasters are added, the result is that we’ve undoubtedly had a bad year.’

President PPK also acknowledges that optimism was too high:

‘I think we were too optimistic and took too long to realize the full extent of the issues we inherited from the past government, which were not clear when you interviewed me last time. Who knew that in the past five years over 80 thousand additional officials had been hired to the central government? This has been revealed along the way and has curbed the government’s effectiveness.’

RECOVERING OPTIMISM

Peru’s political and economic scenario and prospects suffered great setbacks during the first year of governance of President Kuczynski. However and paradoxically, at the onset of year two, some events have occurred that come together to create a cautious possibility that a turning point may be on the way.

The first and most important was the meeting held in the first fortnight of July between President Kuczynski and opposition leader Keiko Fujimori, which led to forecasts that relations between the president and Congress could change from the open battle seen during the first year to a time of greater cooperation without loss of typical tensions inherent in democracies during the second year.

“At the onset of year two, some events have occurred that come together to create a cautious possibility that a turning point may be on the way”

This meeting was the second they have had since elections in June 2016 and, unlike the first, which had no positive outcome, this time some results are taking place that would have seemed impossible to attain only weeks earlier.

To start, after Kuczynski and Fujimori met, both stated that the Congress would review its blocking of several legislative decrees issued by the government on the advancement of concession processes.

The Fujimori majority Congress also approved the government’s proposal to replace the former comptroller general—who was dismissed due to serious breaches of conduct—leading to the appointment of Nelson Shack, a solvency expert who can contribute to the quality of the control system without damaging ongoing investments in Peru, the total opposite of what had been occurring in the past.

In this regard, we should point out that another weakness in Kuczynski’s first year of term was the fight against corruption.

‘The bottom line is not positive, as the president never had this topic on his agenda (…) and I think he has paid the price: Not having been prepared for something that was so clear, which is that Peru is suffering from structural, systemic and generalized corruption, which should be one of the main urgent priorities of any government,’—commented José Ugaz Sánchez Moreno, chair of International Transparency and former ad hoc anti-corruption attorney.

Another sign that government-opposition relations are improving is that in the last fortnight the aggressiveness of the opposition parliament legislators toward the Ministerial Cabinet has reduced, while government statements towards Fujimorism have also been more moderate.

The possibility that this improved understanding between government and opposition will continue hinges however on the hottest topic in Peruvian politics: the debate on the pardon of former president Alberto Fujimori.

This issue has been handled by the government and opposition, but also by Fujimorism, due to the existence of extremely divergent points of view on this issue in the heart of the Fujimori family.

On the one hand, it would be complex for President PPK to grant a pardon to Fujimori due to the nature of the crimes for which he was convicted, as presidential pardon cannot be bestowed when there are crimes for the abuse of human rights. There are however those who believe that the president does not have any constitutional impediment to granting pardon. Based on this argument the head of state is considering the possibility of issuing ‘medical pardon.’

“This improved understanding between government and opposition will continue hinges however on […] the debate on the pardon of former President Alberto Fujimori”

But the topic of pardoning former President Fujimori is also leading to a growing and open confrontation between his two children who are involved in politics and speculation on the possibility that the Popular Force parliamentary legislators will divide between those who follow Keiko and those supporting Kenji.

Apart from this, it is true that after decided open antagonism between the government and the Fujimori opposition in Congress in the last 12 months, the doors are slowly and hesitantly opening for a less unstable scenario than the one experienced in the past year.

In this regard, many believe that there may be space for ‘cautious optimism’ on prospects of economic growth in the next 18 months, such as economist Gianfranco Castagnola, executive president of Apoyo Consultoría, who bases this claim on three factors. The first is the aforementioned dialogue between President Kuczynski and Keiko Fujimori.

The second factor that endorses optimistic forecasts is related to ‘the loosening of public spending as the only tool that could reverse the stagnation in the production sector in the very short term.’ According to Castagnola, one of the main mistakes in the economic policy during the first year of PPK’s government was a counterproductive adjustment to public spending in the last quarter of 2016.

The third factor to nourish optimism is the commissioning of public-private partnerships planned by the new minister of Transport and Communications Bruno Giuffra, along with the redefinition of the role of the general comptroller of the republic that the new holder of this post will assume.

Castagnola concludes that, if these conditions concur, one could think of 7 percent growth in private investment—after four years of falls—and 4 percent for the GDP in 2018.

IN SEARCH OF LOST OPTIMISM

Forty years ago, Pedro Pablo Kuczynski wrote a book that was published by Princeton University and entitled Democracy under Economic Pressure. In the book he described what happened in the first government of President Fernando Belaunde Terry (1963-1968), in which he was the secretary general of the Central Reserve Bank.

This government ended before its time due to a military coup d’état that remained in power for 12 years.

Now history has erected Kuczynski not as a writer but as the president of a nation in which he must direct an economy under political pressure, and the result need not be the same.

The scene is complex, but there are reasons for reviving the optimism felt at the beginning of PPK’s government one year ago, which was lost along the road due to the convergence of a set of political factors that damaged the economy.

At least this is what President Pedro Pablo Kuczynski believes, who after acknowledging that his first year in office ‘was undoubtedly bad,’ partly due to ‘our mistake in underestimating what could happen,’ he now thinks that the second year can be much better.

However, in order for this improvement to take place, this must be the term in which politics manages to organize the economy and not the reverse, as has been Peru’s pattern in recent decades.

In this regard, during the next 12 months, the government of President Kuczynski will continue to seek lost optimism.

This report was written by the Public Affairs team of LLORENTE & CUENCA in Peru.